Tennessee Williams to “Torch Song Trilogy”:

A History of Queer Theatre at La MaMa (1962-1980)

by Pooja Desai

This exhibit, which was created by Pooja Desai, a student in NYU’s Program in Archives/Public history, looks at theatrical experiments from La MaMa’s early years (1962-1980) through a queer lens. Using objects from La MaMa’s Archives, Desai reconstructs a history of the plays, production companies, playwrights, and directors who presented work on La MaMa’s stages that either reflected a “queer sensibility” or were relevant to queer/trans/LGBTQA audiences.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Shows

- People of Interest

- Theatrical Companies

- Sources

INTRODUCTION

“…nobody knows where performance comes from when it’s the text-based theater stuff. And it comes from John Vaccaro, and Jack Smith, and what I call the ‘criminal psychedelic homosexual avant-garde.’” – Penny Arcade

From its beginnings in the late 1950s, off-off-Broadway offered a platform for queer artists who were excluded from both mainstream theatre and the existing avant-garde movement. At Caffe Cino, the oldest of the pioneering off-off-Broadway venues, many of the regular staff and customers were gay, as were many of the playwrights whose plays were performed there. These early off-off-Broadway plays often spoke frankly about and even celebrated marginalized sexualities and gender identities in a way that shocked even the existing avant-garde movement.

Production photograph from Miss Nefertiti Regrets, featuring Jackie Curtis and Bette Midler. Photographer unknown. Click through to see the object’s full catalog record.

As the sixties progressed and the scene grew with the founding of venues like La MaMa, off-off-Broadway remained an important venue for queer expression in theatre. As the quote from Penny Arcade suggests, there were a number of notable artists involved in the early years of the scene whose work reflects a queer interest: John Vaccaro, Harry Koutoukas, Harvey Fierstein, Tom Eyen, Tom O’Horgan, Charles Ludlam, and a number of Warhol superstars including Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and Mario Montez. All of these artists were involved with La MaMa as performers,writers, or directors — or all three.

This exhibit uses materials from La MaMa’s extensive archival collection in order to examine the work these artists did in the early years of La MaMa’s history. In doing so the exhibit hopes to answer some questions about queer theatre, namely: What exactly is queer theatre? What can the works performed at La MaMa tell us about the queer community in New York in the 1960s and 1970s, and what place do these theatrical experiments have in the broader context of queer history?

WHAT IS QUEER THEATRE?

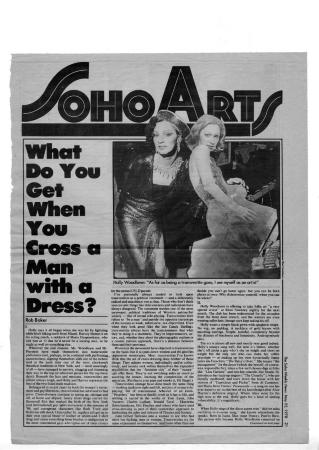

Article by Rob Baker for The Soho Weekly News. Click through to see the whole article and its catalog record.

Pinning down what exactly “queer theatre” is poses a difficult task because it means tackling decades’ worth of of baggage surrounding the idea of queerness in a historical context. Ideas about sexuality and gender identity, as well as the terminology used to talk about queer identities, have changed enormously in the past fifty years. One need look only at Rob Baker’s 1978 article “What Do You Get When You Cross a Man with a Dress?”, in which the author’s use of the term “transvestite performer” includes drag queens, transgender women, and other female-presenting performers who were assigned male at birth. Baker’s language is outdated, and would today be considered inaccurate and offensive. As a historical document, Baker’s article provides insight into the cultural logics that shaped the downtown view of gender nonconformity in the 1970s, particularly for feminine-presenting individuals.

Given these considerations, this exhibit will use two basic definitions of queer theatre as a starting point.

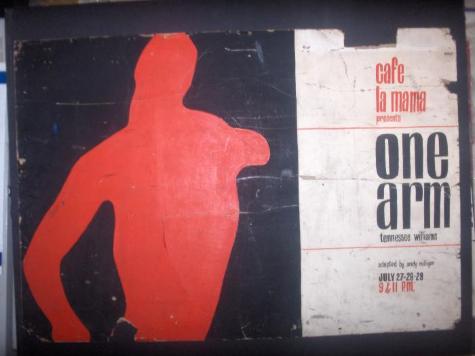

The first definition is: theatre that incorporates queer themes or characters in an easily recognizable way. Plays in this vein include Tennessee Williams’ One Arm, which is about a one-armed street hustler’s struggle to earn a living. Since queerness is, like all identity categories, historically produced, this definition must necessarily allow space not just for characters who self-identify as queer or trans but those whose actions suggest sexualities and/or gender identities other than cisgender and/or heterosexual.

The second, definition is: theatre which reflects a queer aesthetic or sensibility, or holds an interest for a queer audience without necessarily being about issues directly related to sexuality, gender identity, or other overtly queer themes. These plays are not “about” queerness, and may be devoid entirely of explicitly queer or trans characters, but they contain subversive or alternative elements that may speak to non-straight, non-cis audiences. These could be plays that challenge or mock “normative” sexualities and gender identities, which use cross-gender casting, or which embody “camp” aesthetics as a form of social commentary.

This last term, camp, is an important aspect of the style of queer theatre, then as now. As defined by Susan Sontag (“Notes on Camp” [1964]) camp is an almost “private code” of aesthetics based on exaggeration, artifice, and over-the-top theatricality. It celebrates the unnatural and the artificial, but even when it mocks it does so with complete earnestness. Camp sensibility can be seen in many parts of what may be considered “queer culture,” from slang to fashion to films and plays which have become cult classics among queer audiences.

A NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY

As mentioned earlier, the terminology used to talk about queer and trans people and queer/trans issues has changed greatly since the 1960s and 1970s. Certain terms have fallen out of favor or have been lumped under terms like “queer” or “gay” or “trans,” but using only umbrella terms poses the danger of erasing identities that may no longer be part of mainstream LGBTQ+ discourse. For this reason, certain decisions have had to be made about which terms to use in order to make the exhibit accessible while also remaining true to historical context.

When it comes to identity terms, the exhibit will use specific terms if the person being written about uses those terms to describe themselves. When this is not the case, more general terms may be used in order to place a figure or their work within a queer context without making assumptions about their identity. While I do acknowledge that using general terms like “queer” or “trans” in this way is anachronistic, it is necessary to make this exhibit searchable for modern readers who may not be aware of the nuances of sexuality- and gender-based terminology.

When it comes to pronouns, the exhibit will use whatever pronouns seem to be most frequently used to refer to an individual unless there is evidence that they prefer a particular pronoun.

Finally, this exhibit does not intend to “out” any person who was not open about their sexuality or gender identity in their lifetime. When a show is coded as queer in this exhibit, I am referring to the content or style of the play, not the actors, writers, or directors. If an actor, writer, or director is talked about as being queer, it is because they publicly associated themselves with a queer identity. Assumptions will not be made regarding the gender identity or sexuality of anyone mentioned or depicted in this exhibit.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF QUEER THEATRE AT LA MAMA

La Mama’s association with queer theatre began in 1962 with its very first staged performance, which was an adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ short story-turned-screenplay One Arm. The sexuality of the main character, a one-armed street hustler, is ambiguous: although his romantic attachments are chiefly with women, he is not entirely detached emotionally from the men that he sleeps with for money. In any case, the fact that the play centers on a man who has sex with men gave the play a queer interest, particularly considering its frankness on the subject for the time period in which it was performed.

A number of theatrical productions with queer themes followed over the next few decades. The Playhouse of the Ridiculous–a La MaMa Resident Company–debuted in 1965, and though its director John Vaccaro dismissed the notion that his plays were “something homosexual,” the plays his company put on nonetheless challenged mainstream sexuality and gender through role reversal and cross-gender casting.

Vaccaro was by no means the only director to use cross-gender casting and drag in his plays. All three productions of Jean Genet’s play The Maids staged at La MaMa in its earliest years cast male actors as the two maids, as Genet apparently intended, in order to subvert audience expectations and draw their attention to the role reversals that take place in the play. And off-off-Broadway luminary Harry Koutoukas, whose insistence on referring to his plays as “camps” says a great deal about the queer style of the plays, cast a male actor in the role of the titular queen in his version of Medea, which he called Medea in the Laundromat.

Other plays focused on different forms of role reversal outside of drag, such as The White Whore and the Bit Player, and yet other plays used different aspects of camp sensibility either as satire or merely as a form of attacking social conventions, as did the works of Charles Ludlam. These plays were not always about queer content–that is, characters who are queer or who exhibit queer behaviors–but their experimental, subversive nature provided a setting for the creation of community ties within the queer underground. Even if the play itself was not queer, the audience was there because they–and sometimes the playwright, director, and actors–had queerness in common.

THE MAIDS

Jean Genet, author of The Maids, wrote in his novel Our Lady of the Flowers: “If I were to have a play put on, in which women had roles, I would demand that these roles be performed by adolescent boys.” According to Tom O’Horgan, his 1964 production of Jean Genet’s play The Maids at La MaMa was the first in America to fulfill the playwright’s intention. This first production, which was also the first show O’Horgan directed at La MaMa, was received with some confusion by critics, who did not understand the purpose of having what some observers called “transvestites” in the main roles. Sydney Schubert Walter, reviewing the play in The Village Voice, thought it was confusing that the play’s two maid characters were played by men but the Madame was played by a woman, because it contradicted his idea of the play as a transvestite “fantasy.”

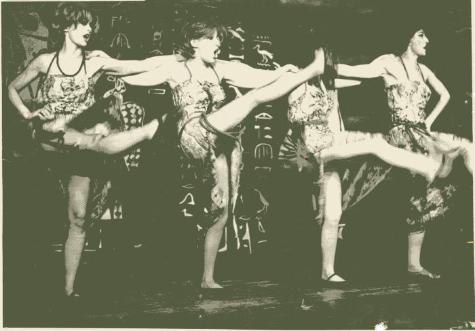

Production photograph by James Gossage, 1965. Click through to see the full catalog record for this object.

What this review misses is that the point of cross-gender casting in The Maids was to draw attention to and destroy the illusion of theatrical role-playing. The 1964 production begins with the actors “getting into drag,” which was designed to remove any sense that the actors and the characters who they played on stage are one and the same. The Maids, according to Ozzie Rodriguez (Director of La MaMa’s Archives), forces the audience to accept the arbitrariness of the roles in the play, first through the presentation of the men in drag and then through the class-based role reversals as the maids in turn take on the role of Madame. The cross-gender casting works with the characters’ role-playing to make the ultimate point of the play: that roles are forced upon individuals, and that there is nothing that separates two lowly maids from their upper class Madame except for the fact that society has made it so.

A Village Voice review of the 1965 production emphasizes that these actors are men, not adolescent boys as Genet intended, but the fact that they are so obviously men enhances the performance. “They are not pretty,” writes author S.S., “but this is not a pretty play and through their performances the full power of ‘The Maids’ comes into alarming focus.” The 1971 revival of the play, co-created by Jimmy Wigfall, cast men in all three parts — further emphasizing the interchangeability of the characters’ social roles — but it still maintained the artificiality of the actors’ drag.

MEDEA IN THE LAUNDROMAT

Production photograph, 1965. Photographer unknown. Click through to see the catalog record for this object.

Playwright Harry M. Koutoukas insisted on calling his plays “camps” — which says a great deal about the style and content of the plays in question. In fact, Medea in the Laundromat, a modern, urban version of the Classical myth of Medea, appeared a year after Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” popularized the term. In terms of its plot, the play (or rather, the camp) follows the basic storyline of the myth, but it is is filled with incongruous elements. The title role is played by a man, Charles Stanley, with dramatic, theatrical gestures. Despite the play’s modern setting, the language is highly formalized in a pastiche of declamatory Greek verse. The characters in the play are aware of Medea’s myth before it happens, and she herself references the fact that she knows how her story ends.

These incongruities are a vital part of the camp aesthetic, which often depends on seriousness or earnestness in the face of ridiculous circumstances. In camp comedy, this often takes the form of delivering ridiculous lines in a deadpan manner; but Koutoukas maintained that camp is “deadly serious.” The inherent ridiculousness of a figure from Classical mythology killing her children by putting them in a washing machine is contradicted by the earnestness of the performances. The play has a sense of pathos which brings it into the realm of camp tragedy. Its incongruities serve to create the sense of a world that is insane and out of order. Medea in the Laundromat’s many contradictions of style and content emphasize the collapse of order in the face of Fate, thereby creating a modern version of Greek tragedy.

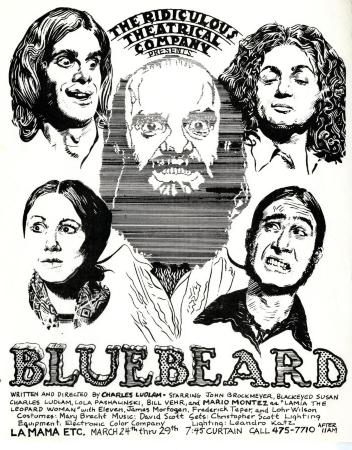

BLUEBEARD

Like many of Charles Ludlam’s plays, Bluebeard, produced by his Ridiculous Theatre Company at La MaMa in 1970, is a camp pastiche. The play, a take on the French folktale about the man who murders his successive wives, is turned by Ludlam into a mix between Victorian melodrama and B-movie horror. Ludlam’s Bluebeard is not only a murderer but a mad scientist who conducts medical experiments on his wives — one of whom was played by Warhol superstar Mario Montez — in an attempt to create a “third sex.”

The plot element of the medical experimentation reveals the play’s satirical undertones. Bluebeard’s attempts to create a “third sex” reference Victorian “quasi-scientific” attitudes toward sexuality and gender which conflated homosexuality with an inability to perform expected gender roles. The wife played by Mario Montez is a failed experiment who does not know whether she has “a mound of Venus or a penis,” and the play ends with Bluebeard’s latest wife Sybil (played by Black-Eyed Susan) appearing with an ambiguous “third genital.” Despite the many trappings of both camp sensibility and ridiculous theatre — from the bright blue beard Charles Ludlam wore in the title role to the melodramatic use of the title “House of Pain” for Bluebeard’s torture chamber — the play works as a dark satire of historical pseudoscience.

HEAVEN GRAND IN AMBER ORBIT

Production photograph from the 1976 revival of Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit. Photographer unknown. Click through to see the full catalog record.

Jackie Curtis’s play Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit, directed by John Vaccaro and performed by the Playhouse of the Ridiculous, received mixed reviews, to say the least. A review by Martin Washburn in The Village Voice calls it a “melodious freakfest” which “has the allure of a dung popsicle.” A Newsweek review of the same production says much the same, but with a more positive bent, celebrating the play’s madcap style and positioning its obscenity and tactlessness in the context of a deliberately freakish attack on the sanitized popular image of 1960s America. It contains, among other things, “transvestism, scatology, obscenity, camp, self-assertion, self-deprecation, gallows humor, cloacal humor, sick humor, healthy humor, and cutting, soaring song,” most of which were hallmarks of Vaccaro’s style of Ridiculous Theatre.

In fact, the play’s bad taste made it somewhat notorious, with several reviews and analyses of it making a point of mentioning the fact that the play included a thalidomide baby and a set of Siamese twins joined at the anus. The play’s fixation on freakishness and mutation is a deliberate choice meant to bring out the “underside” of American society, the “children of the 60s” who are too monstrous to exist but insist on doing so anyway.

Vaccaro, a rather difficult director, kicked Jackie out of a production her own play in much the same way he did to Charles Ludlam in Conquest of the Universe. Curtis did, however, appear in the 1976 revival, which was somewhat more subdued but lost none of the spirit of the original production.

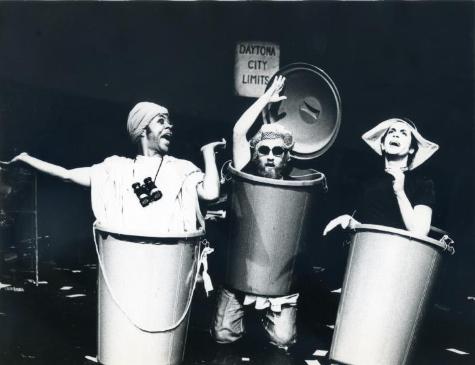

THREE DRAG QUEENS FROM DAYTONA

The Tom Eyen play Three Drag Queens from Daytona, staged at La MaMa in 1973, combined camp with absurdism. The play starred James Wigfall, Peter Bartlett, and William Duff-Griffin as three aging drag queens residing in trash cans near Coney Island.

Reviews compare the play to Absurdist Theatre in the vein of Samuel Beckett, saying that the three drag queens, as they sit around “bitching … and dishing,” seem to be “waiting for Godot.” The play is a pitch-black comedy full of overt social and political commentary, but it also contains references to old pop songs, movies, and other sorts of nostalgic pop culture. These references shift the play’s tone towards the camp — though in many ways the camp sensibility of the play exists in the very balance between the dead-serious social commentary and the flippant pop culture references. Lines like “Watch it, Edna, you’re denting the emeralds” are witty on their own, but even more so when set against the other, darker parts of the play.

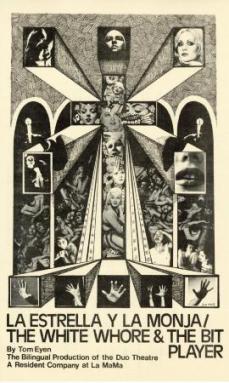

THE WHITE WHORE AND THE BIT PLAYER

The White Whore and the Bit Player characteristic of Tom Eyen’s plays in that it reflected his fascination with Hollywood glamour. In this case, the play, whose action takes place in the protagonist’s imagination in the seconds before her death, draws on the unhappy lives of classic Hollywood starlets like Jean Harlow and Marilyn Monroe.

There is nothing in the actual content of The White Whore and the Bit Player that makes it queer; but, like Genet’s play The Maids, its themes and social commentary hold a queer interest. The exchange of roles between the nun and the white whore, which occurs when the nun dramatically removes her habit and thereby takes on the whore’s identity, recalls the role-playing in The Maids, wherein Solange and Claire take turns playing the role of Madame. The sheer contrast between the two roles, and the way they become intermingled as the white whore’s life flashes before her eyes, serves as commentary on the arbitrariness of these roles.

Program for the bilingual Duo Theatre production, 1973. Click through for the catalog record of this object.

Like a number of other plays by Eyen, The White Whore and the Bit Player drew gay or otherwise queer audiences because it reflected themes relevant to their lives despite its lack of gay or queer characters. It was “not a gay play,” says Ozzie Rodriguez, but “he [Eyen] had to be gay to write it.”

The bilingual production by the Duo Theatre, a resident company at La MaMa, notably featured Warhol superstar Candy Darling as the white whore in the English language version. Duo Theatre co-founder Magaly Alabau, a Cuban-American poet and actor who later helped create the lesbian theatre company Medusa’s Revenge, played the same role in the bill’s Spanish language version.

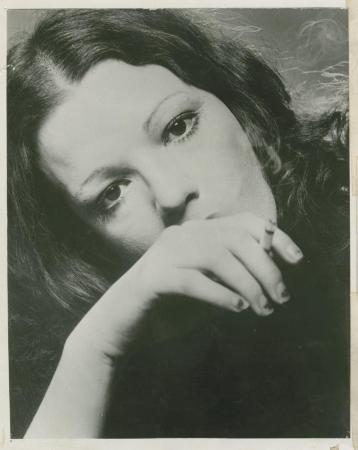

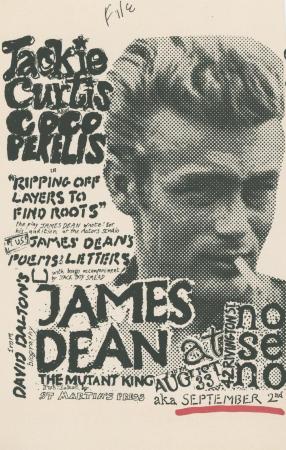

JACKIE CURTIS

Jackie Curtis was a playwright, actor, Warhol superstar, and friend of Ellen Stewart and La MaMa generally. She was involved in a number of plays at La MaMa as either performer, playwright, or both, from the early production Miss Nefertiti Regrets to her own plays Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit; Vain Victory, or the Vicissitudes of the Damned; and Champagne. A number of her plays starred people who were, or who would go on to become, known outside of off-off-Broadway, such as punk rock musician Patti Smith, who starred in Curtis’s Femme Fatale; Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn and actress Penny Arcade, who starred in Vain Victory, or the Vicissitudes of the Damned; and actor Robert de Niro, who starred in Glamour, Glory, and Gold. Her plays betrayed an obsession with Hollywood and its scandals, particularly Glamour, Glory, and Gold, which tells a classic story that is as old as film itself: that of the aspiring starlet struggling to get her foot in the door.

Flyer for a production of the James Dean play Ripping Off Layers to Find Roots starring Jackie Curtis and Coco Perelis. Date unknown. Click through to see this object’s catalog record.

In a poster for the performance Jackie Curtis Sings, Curtis is described as “The Quintessence of Ambiguity,” and this is a perfect summary of the way in which she thought about herself. She deliberately chose not to label herself in terms of sexuality or gender identity. Quoted in the New York Times in 1969, she laughed off the concept of someone feeling like “a woman trapped in a man’s body,” adding, “What is a man? What is a woman?” She went on to describe sex change operations as being “so 1950s.” Speaking to The Herald in 1971, she said, “I never claimed to be a man, a woman, an actor, an actress, a homosexual, a heterosexual, a transsexual, a drag queen… Clothing merely expresses a mood, reflects a person’s most mysterious qualities.” Her decision to don feminine clothing had nothing to do with wanting to “pass” as a woman and was instead a way of expressing certain facets of her personality.

Though Curtis was known for her unique rock-and-roll style of female drag (the New York Times excerpt quoted above goes into great detail about one of her everyday outfits, which consisted of “a miniskirt, ripped black tights … clunky heels,” and “no falsies”), she also performed and lived in male drag. Her obsession with classic Hollywood glamour could also be seen in her masculine performances, which reflected the sensitivity of James Dean or Montgomery Clift rather than traditional masculinity.

JOHN VACCARO

When John Vaccaro formed the Playhouse of the Ridiculous in 1965, it was to “get away from” what he called the “soap operas” of commercial theatre. Like many of the experimental artists involved with La MaMa and with off-off-Broadway generally, he was bored with mainstream theatre and sought to break all its conventions. He accomplished this by pioneering the genre of the theatre of the ridiculous, a progression from the Theatre of the Absurd which challenged society’s stagnant conventionality through over-the-top, chaotic performances and controversial, confrontational subject matter. Vaccaro often used what may be considered elements of queerness to achieve this, such as cross-gender casting and camp aesthetics, but he insisted, time and time again, that he “didn’t do it as a homosexual thing.” He meant it instead as a commentary on the artificiality and arbitrariness of social roles.

Though Vaccaro was derided by Charles Ludlam as being “too conservative”, the shows he directed did not by any means escape controversy. When the Playhouse of the Ridiculous performed in Belgium, Vaccaro and several of the actors were arrested on the basis of the indecency of the performances, whose props included “giant phalluses.” This prop comes from the play Cock-Strong, a play which deals heavily in problems with virility and lack thereof: the male lead is arrested for not being able to perform his masculine role, and at one point he is fined five dollars for laying an egg.

The incident in Belgium was perhaps an extreme example of the reaction Vaccaro’s plays garnered, but other plays he directed — such as Jackie Curtis’s Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit, which was infamous for its use of “freakish” characters like amputees and conjoined twins — also received mixed responses from critics and audiences for their outrageous, camped-up content.

CHARLES LUDLAM

Playwright, actor, and director Charles Ludlam began as a member of John Vaccaro’s Playhouse of the Ridiculous until a falling-out between the two prompted Ludlam to leave the company. In 1967 Ludlam formed his own theatrical company, the aptly-named Ridiculous Theatre Company, which showcased his own version of the ridiculous theatre tradition.

Small poster for Conquest of the Universe. Date unknown. Click through for the catalog record of this object.

The company had an overtly theatrical, deliberately artificial style born out of Ludlam’s dislike of anything that talked down to its audience. Many of Ludlam’s plays took the form of pastiche, and the dialogue for plays like Big Hotel and Conquest of the Universe, both parodies of existing works, was made up almost entirely of quotes and paraphrases from old movies and comic books. Big Hotel, predictably, lifted much of its content from the Greta Garbo film it parodied, Grand Hotel; but it also borrowed from such disparate sources as the film adaptation of Wilde’s Salome, Playboy cartoons, television commercials, and old Wonder Woman comics. Conquest of the Universe, a parody of Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great, shared some of the same sources, as well as The Canterbury Tales, science fiction novels, and “S&M pornography.”

As the last of these sources may suggest, Ludlam’s plays were not shy in the least about sexuality. He thought commercial theatre was “disgusting” for its conventionality, believing that was not the purpose of theatre to teach morality to its audience and that “heterosexuals gave up the right to moralize when they accepted the pill and abortion.” As this quote suggests, the sexual explicitness of his plays is inextricably tied up with their queerness. Ludlam sought to question sexual mores, and according to him, “at that time the gay community was the most sexually liberated. The impact of gay attitudes on culture has been very great.” Like Vaccaro and his Playhouse of the Ridiculous, Ludlam and his Ridiculous Theatre Company used the external trappings of gay or homosexual culture as a way of making a greater point about society and its adherence to arbitrary conventions, but Ludlam was much more willing to claim the term as a descriptor of his work.

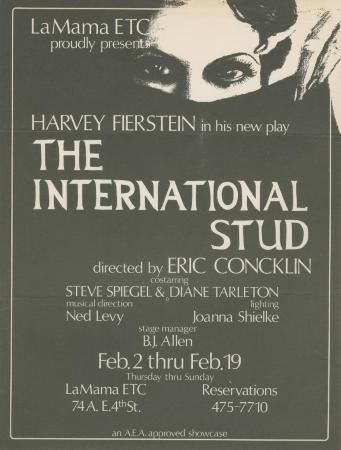

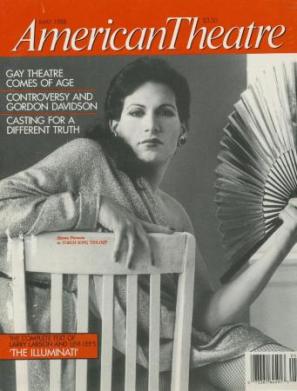

HARVEY FIERSTEIN

Harvey Fierstein in drag for Torch Song Trilogy on the cover of American Theatre, May 1988. Click through for related article.

Harvey Fierstein is now known as a Tony Award-winning actor and playwright, but he made his acting debut at La MaMa in the Andy Warhol play Pork. He has had a wildly successful career that has included a number of queer or queer-adjacent roles, including the male lead in the play for which he won his Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play, Torch Song Trilogy.

The first two acts of Torch Song Trilogy, The International Stud and Fugue in a Nursery, were first staged at La MaMa in 1978 and 1979, respectively. The play centers on three different points in the life of a Jewish drag queen named Alan who, as the title suggests, makes a career of singing torch songs. Torch Song Trilogy centers on the themes of community and family as Alan deals with both romantic and familial relationships. The play was groundbreaking for its time in that it succeeded in taking such “exotic” subject matter as the life of a gay drag queen and making it relatable to non-queer audiences. The play portrayed gay life as something that was part of the rest of society rather than something that occurred in isolation, removed from the unseeing eyes of straight society.

Fierstein’s second Tony Award for acting, the Award for Best Leading Actor in a Musical, was, like his first, awarded to him for a role that relies heavily on drag: Edna Turnblad in Hairspray. He blamed his penchant for drag performances on an acting coach he once had who apparently told him “he’d never be a leading man, so he might as well try something else.” He never identified as a woman, but he was open about being particular type of gay person: “Say I’m a gay activist or a queen out of her time, I don’t care…. That’s it–I should have been a 1990s video star.”

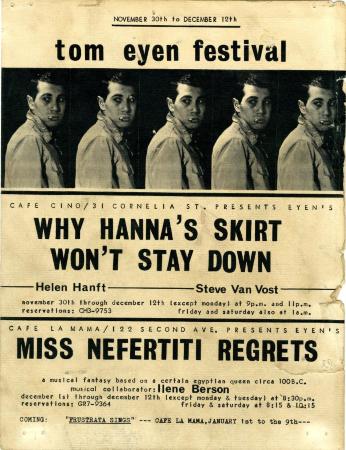

TOM EYEN

Promotional poster for the Tom Eyen festival (1965), advertising two of his plays at two locations: La MaMa and Caffe Cino. Click through to see this catalog record for this object.

Tom Eyen was one of the auteurs who emerged out of the late 1960s and early 1970s, directing and starring in his own works in much the same way that Charles Ludlam and John Vaccaro did. Founder of the Theatre of the Eye Repertory Company, Eyen was known for his kaleidoscopic staging and abstract, surrealist style, as well as the bold sexual content of his plays and his apparent obsession with fame and Hollywood. He worked in Broadway, Off-Broadway, and off-off-Broadway, and the plays he directed at La MaMa included Why Hanna’s Skirt Won’t Stay Down, The White Whore and the Bit Player, Three Drag Queens from Daytona, and Miss Nefertiti Regrets, the last of which gave Bette Midler her first professional role.

Though few of the plays Eyen was involved with were “gay” plays in the sense of having queer subject matter, his plays were highly relevant to a queer audience for a number of reasons. Like Ludlam and Vaccaro, he was tired of the conventionality of mainstream theatre and wished to subvert it and its tropes. A play like The White Whore and the Bit Player, one production of which starred Warhol superstar Candy Darling, is not about a gay or queer subject, but the role reversal between the “white whore” and the nun is a subversive attack on the audience’s expectations of what these roles mean. Productions of such plays became an important point of contact in the queer underground because of the level of plausible deniability.

Eyen saw himself as “outrageous,” and for him part of being outrageous in opposition to conventional theatre was embracing that which mainstream audiences might consider freakish or otherwise unacceptable. He considered this to be the way forward, saying that he believed “a serious transvestite could be [our heroine]…the ‘70s are drag.”

THE PLAYHOUSE OF THE RIDICULOUS

When John Vaccaro’s Playhouse of the Ridiculous debuted in 1965, it pioneered a new genre of theatre known as the “Theatre of the Ridiculous.” A genre that had its roots in the earlier Theatre of the Absurd, the goal of ridiculous theatre was to draw attention to what was artificial in theatre — and in life. The style of the Playhouse of the Ridiculous was, as the name suggests, non-serious, with purposely anarchic and unstructured performances in which actors were allowed and even encouraged to make mistakes.

Photo collage of the Playhouse of the Ridiculous. Date unknown. Click through for the catalog record for this object.

One major part of the Playhouse’s anarchic style was role reversal, and a major component of this was Vaccaro’s decision to cast male actors as female characters, and vice versa. According to Vaccaro, his reason for casting men in female roles was that “he was better at it than a woman was. He could play it better.” The same must have been true of a woman playing a man’s role, for Vaccaro often cast Mary Woronov in masculine roles, including Tamberlaine the warlord in Charles Ludlam’s Conquest of the Universe. Critic Stefan Brecht, in reviewing the genre of ridiculous theatre, felt that cross-gender casting was used to such a degree that it “strikes one as peculiar when an actor plays his own sex.” Vaccaro himself was not necessarily trying to make a political statement; the hilarity of seeing a very masculine performer attempt to appear feminine was just another facet of the overall ridiculousness of ridiculous theatre. Nonetheless the use of cross-gender casting drew attention to the arbitrariness of gender roles by reproducing them in ironic ways.

Plays produced by the Playhouse of the Ridiculous include Charles Ludlam’s earlier play Big Hotel, both productions of Jackie Curtis’s Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit, Tom Murrin’s Cock-Strong and its follow-up Son of Cock-Strong, XXXXX, and a show interestingly titled The Sixty Minute Queer Show. The shows were often deliberately confrontational and generated controversy on numerous fronts. Cock-Strong was famous for its use of a giant phallus as a prop — the same prop that got the Playhouse of the Ridiculous arrested in Belgium — and Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit shocked many with its portrayal of a thalidomide baby, Siamese twins, and a stump-armed princess played by John Vaccaro.

Though Stefan Brecht claims that ridiculous theatre was “by and for queers,” Vaccaro maintained that the Playhouse was not meant to be queer — a claim which led Charles Ludlam to accuse Vaccaro of being “too conservative.” Instead, Vaccaro used queer themes as a way of confronting and mocking mainstream ideas about sexuality and gender. In doing so, he made queerness a vehicle for expressing the nihilist, absurdist philosophy of ridiculous theatre.

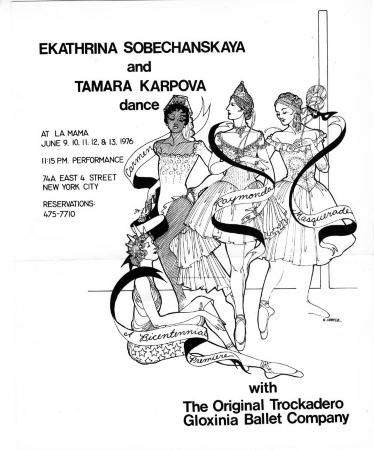

THE TROCKADERO GLOXINIA BALLET COMPANY

Poster for the Trockadero Gloxinia Ballet Company’s performance of the Carmen Raymondo Masquerade, 1976. Click through for the full catalog record of this object.

The all-male Trockadero Gloxinia Ballet Company is unique among the many examples of drag and cross-dressing in this exhibit for its surprising lack of irony. On the surface, the Company displays many of the trappings of a camp sensibility: from ostentatious costumes, to the rather grandiose name of the company itself, to the decision of many of its performers to take elaborate Russian stage names which were clearly meant to hearken back to the famous Ballets Russe.

There was certainly an element of parody to their whole aesthetic, but according to Stefan Brecht, the company’s performance style was “definitely not camp” (his emphasis). Though the performers’ imitation of classic ballet meant donning female costume, not to mention wigs and makeup, female impersonation was not the goal. Rather than putting on drag for its own sake, the performers were trying to capture the style and aesthetic of a specific type of dance. Their attitude towards the gender they performed was so ambiguous as to create what Brecht calls a “transcendence of gender.”

CONCLUSIONS

These various theatrical experiments give us a huge array of historical ideas about sexuality and gender, as do the words and lives of the people who created them. In many ways these ideas are at odds with our modern conception of what it means to be queer, or trans, or any other part of the LGBTQA umbrella, but they reveal a great deal about what the things we now consider “queer” meant in the 1960s and 1970s.

The gay scene in New York in the 1960s was an underground whose gathering places were those which were outside the realm of “mainstream” society. Off-off-Broadway became one of those places from its very inception, with the Caffe Cino playing host to gay audiences and artists alike. At La MaMa and Caffe Cino, perhaps the most queer-friendly of the four main off-off-Broadway venues of the 1960s, artists were able to put on plays which, even if they were not queer in their content, appealed hugely to queer audiences. Even those who did not consider their work “homosexual,” like John Vaccaro, nonetheless used apparently queer aesthetic choices like cross-gender casting or camp mannerisms because of their potential as a vehicle for rebellion against the conventions and values of the mainstream.

These theatrical experiments spoke to queer audiences in a way that mainstream theatre often did not or could not, and in doing so they also provide commentary on ideas about gender and sexuality in the New York underground of the pre- and immediately post-Stonewall era. The attempt to pin down what exactly “queerness” meant before that identity terms came into popular use becomes even more difficult when faced with artists whose work challenges the mainstream discourse of not only their own time but ours as well. Some artists were quite open about what their plays were trying to do: Charles Ludlam, who openly embraced the idea of his work being “gay,” presented his work in opposition to what he saw as heterosexual “moralizing” from a society that had made birth control available to straight women but still shamed anyone who did not have the right kind of sexuality. However, it is not always so easy. Someone like Jackie Curtis, who did not define herself as either man or woman, homosexual or heterosexual, “transsexual” or “drag queen,” defies all categories, and is just as ambiguous now as she was then.

It becomes necessary, then, to approach the personalities and works of this moment in history with an open mind — as an audience.

SOURCES

Baker, Robb. “Off-Off and Away.” After Dark, October 1973.

Baker, Robb. “What do you get when you cross a man with a dress?” The Soho Weekly News. May 25, 1978.

Bottoms, Stephen. Playing Underground (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006).

Brecht, Stefan. Queer Theatre (Methuen, 1986).

“From Greenlawn to the Ridiculous” in Newsday. June 4, 1974.

LeSeur, Joseph. “Theatre: The White Whore.” The Village Voice. December 22, 1966.

Rodriguez, Ozzie (Archives Director). Personal interview. April 18, 2016.

Shewey, Don. “Gay Theatre Grows Up.” American Theatre. May 1988.

Topor, Tom. “Theater Pitching Tent on Old Camp Grounds.” The New York Post. July 6, 1974.

Washburn, Martin. Untitled. The Village Voice. October 16, 1969.